Clockwise from top left: Maya Deren, Samira Makhmalbaf, Lucille Ball, Thelma Schoonmaker, Whoopi Goldberg and Julie Harris

Jane Arden (1927-82)

Can it be that the 1970s only recorded one instance of a woman solo directing a British feature film? Sue Clayton made The Song of the Shirt in 1979 and Laura Mulvey made Riddles of the Sphinx in 1977, but both worked collaboratively (with Jonathan Curling and Peter Wollen respectively). Sally Potter’s Thriller appeared in 1979, but its short duration presents no challenge to Jane Arden’s anarchic and brutal The Other Side of the Underneath (1972).

Jane Arden

That alone singles her out as an extraordinary talent, but there’s so much more: she co-wrote 1955’s ITV comedy Curtains for Harry with Dick Lester; gave Charles Laughton his final role, and Albert Finney his first, in her 1958 play The Party; refused to let Salvador Dalí bully her in Dalí in New York (1966); starred with Harold Pinter in a BBC adaptation of Sartre’s Huis Clos (1964); authored the anti-psychiatry-infused prose-poetry volume You Don’t Know What You Want, Do You? (1978); and wrote and sang the disconcerting theme song to her collaborative film Anti-Clock (1979). It’s impossible to say what else she would have done had she not taken her own life at the age of 55.

Sam Dunn

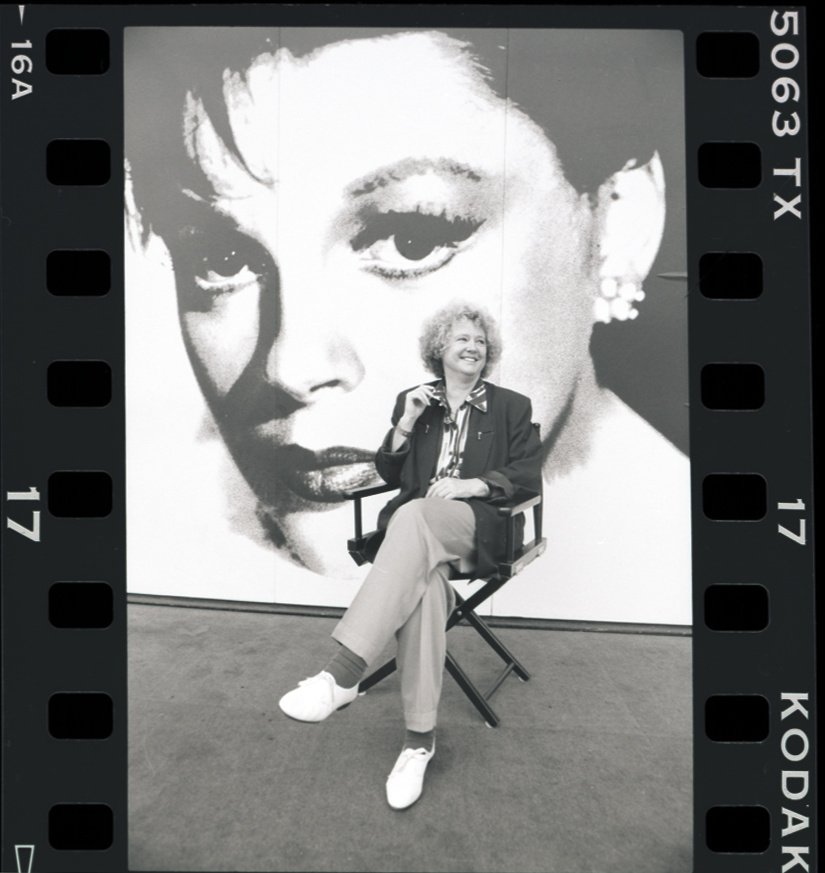

Lucille Ball (1911-89)

Lucille Ball

Her hair was red and curly, and her lips over-painted, but Lucille Ball was no ordinary clown. As Lucy Ricardo in I Love Lucy, she elevated the American sitcom housewife to an almost Beckettian figure: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” And, in her various schemes to join the nightclub act fronted by Ricky Ricardo (her on-screen husband played by her then husband Desi Arnaz), she failed hilariously.

Aged 15, Ball was so anxious that she was asked to leave the John Murray Anderson-Robert Milton Dramatic School after a term. However, with supporters such as Edward Sedgwick and Buster Keaton, she would become one of television’s biggest stars in the pioneering I Love Lucy. She was not only a gifted physical comedian but also the first female Hollywood studio president of the sound era. We have her Desilu Studios to thank for Star Trek.

Adrienne Rashbrook-Cooper

Joy Batchelor (1914-91)

Joy Batchelor’s pioneering career as an animator, director, designer and producer in British animation makes her an inspirational figure. Her achievements are often overshadowed by the presence of her life and business partner John Halas, but the company they founded together, Halas & Batchelor, was founded on their mutual strengths.

Joy Batchelor

Joy defined the look of Britain’s biggest animation studio of the 1940s and 1950s, and provided its voice through her scripts and storyboards. The background characters in New Town (1948) remind me of favourite New Yorker cartoonists of the period, or the more modern renderings of such styles by Seth. The vast majority of her career was in the field of sponsored filmmaking, adding to her relative obscurity, but her centenary year will hopefully mark a rediscovery of her life and work as it is explored and celebrated through the remarkable efforts of her daughter Vivien.

Jez Stewart

Leigh Brackett (1915-78)

The screenwriter and sci-fi and detective fiction novelist Leigh Brackett had her big break in Hollywood in the mid-1940s after the director Howard Hawks hired her to work on the adaptation of The Big Sleep (1946), on the strength of her punchy dialogue. Famously he called her agent thinking that Leigh was a ‘he’ only to discover the truth on meeting: “In walked a rather attractive girl who looked like she had just come in from a tennis match. She looked as if she wrote poetry. But she wrote like a man.”

Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in The Big Sleep (1946), co-written by ‘this guy Brackett’

Brackett was a big fan of muscular writers such as Hemingway, Chandler and Hammett and was to end up as a respected writer in the male-dominated genre that interested her. Crucially, she also put tough-talking female characters like herself in the scripts she wrote for Hawks, whether Vivian Regan (Lauren Bacall) in The Big Sleep or Feathers (Angie Dickinson) in Rio Bravo (1959). Her brilliant career lasted into the 1970s with her final two films, The Long Goodbye (1973) and The Empire Strikes Back (1980), ensuring her a place in the pantheon.

Lizzie Francke

Catherine Breillat (1948-)

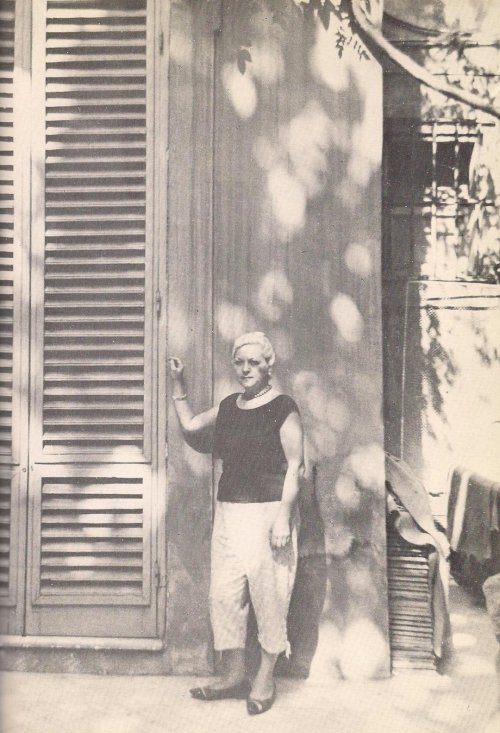

Catherine Breillat

The films of writer, director and non-straightforward feminist Catherine Breillat have had a huge impact on me; even today, whenever I rewatch any of them, I still feel she is talking directly to me and explaining some of the things that matter most in intimate relationships. Her films are a rage against conventional ideas of sexuality, eroticism, pornography and obscenity. Her depictions of female sexual awakening, desire and sense of guilt are unique, poetic, honest, shocking and unforgettable.

My favourites are 36 Fillette (1988), in which a rebellious 14-year-old girl on a family holiday in Biarritz agonises over whether to have sex for the first time with an older guy, and À ma soeur (2001), about two teenage sisters’ contrasting experiences of losing their virginity. The sexual encounters experienced by the characters are brutally realistic, and full of unexpected and complex meanings. Given society’s concern with the influence of pornography on adolescents, it seems to me her films are more relevant than ever, and offer the perfect way to initiate a modern conversation on matters of desire.

Marijose de Esteban

Maya Deren (1917-61)

Kiev-born filmmaker Maya Deren was one of the most influential members of the surrealist and poetic avant-garde film group in 1940s American culture. She belongs to a generation of avant-garde filmmakers who were poets and writers, including Sidney Peterson, Jonas Mekas and Willard Maas. Her now classic debut film Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) is a daring work evoking psychodrama and our many selves.

Maya Deren

A journalist for much of her career, Deren was also a dancer, lecturer and photographer concerned with the social value of documentary film. With André Breton, John Cage, Anaïs Nin and Marcel Duchamp in her social circle, she experimented with naturalistic sound cinema, montage structure and the camera’s ability to capture reality. Despite her short life, Deren produced a diverse body of work moving from psychodrama to ethnographic film. Her camera-eye-vision in Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti (1977) is an influential study of Caribbean dance and magic. A relentless promoter and distributor of experimental filmmaking, Deren promoted avant-garde cinema through her writings, lectures and films and she directly inspired a new generation of boundary-pushing filmmakers including Kenneth Anger and Stan Brakhage.

Georgia Korossi

Jihan El-Tahri (1962-)

Jihan El-Tahri

Our screening of Jihan El-Tahri’s Cuba: An African Odyssey (2007) gave rise to the title for the on-going BFI Southbank strand African Odysseys. This rich and far-reaching tale of Cuba’s involvement in the anti-colonial struggle of African nations combined analysis and insight with an instinctive ability to select and transform archive, while turning it into a fresh, coherent and compelling narrative film. It delighted and inspired the audience and indeed so popular was the film that we had to follow up with a repeat screening. Jihan’s work next appeared at the 53rd BFI London Film Festival with a study of the post-apartheid South Africa ANC Government, Behind the Rainbow (2009). She has also made films about the Middle East, including House of Saud (2004).

Jihan gave a moving and spirited contribution to a panel about Tahrir Square at the beginning of our BFI Arab cinema strand last November, declaring herself an Egyptian but also an African woman and expressing her determination to tell the stories that relate to this region. In person she’s as knowledgeable and as articulate as her films and has a wicked sense of humour. When we spoke in November she was working, defiantly in the face of the political turmoil and oppression in Egypt, to complete an ambitious documentary film history of modern Egypt (Egypt’s Last Pharoahs), which we await with much expectation.

David Somerset

Mary Field (1896-1968)

If there’s one great unwritten biography in British film, it’s Mary Field’s. Unique in her generation of women, she progressed from hands-on filmmaking to senior industry roles, en route linking several cinematic highways and byways. Field was above all a formative figure in filmed natural history (via the much-loved Secrets of Nature and Secrets of Life series of pre-war cinema shorts), educational filmmaking (her film teaching aids spanned the 1930s curriculum) and children’s cinema (the first head of the legendary Children’s Film Foundation; incidentally, Field had no children herself).

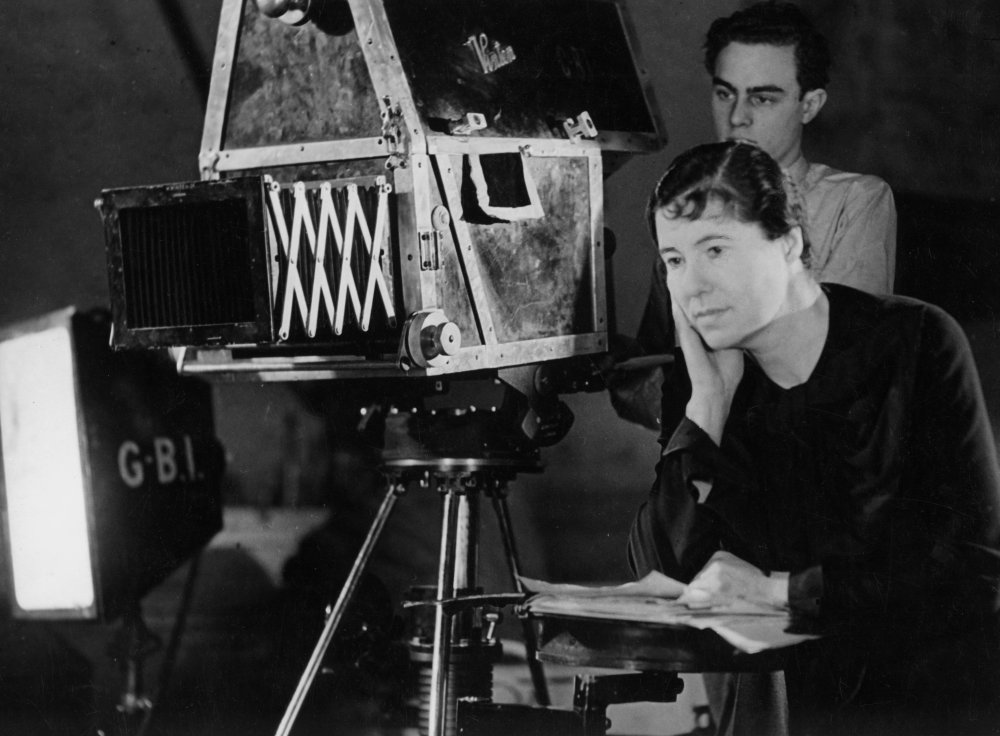

Mary Field

Mary Field was no radical: a figure of her time, she today cuts a slightly forbidding, old-fashioned figure out of keeping with streetwise modern childhoods: sort of a cinematic Enid Blyton. But what a legacy! It lurks both in children’s TV and natural history filmmaking – which, undeniably, is one of Britain’s profoundest professional contributions to the moving image age.

Patrick Russell

Whoopi Goldberg (1949-)

Whoopi Goldberg is a maverick. She has an Oscar, Grammy, Emmy and Tony award to prove it, and in the 1990s was momentarily the highest-paid actress in Hollywood history. But her admirable qualities lie beyond award-shaped success; after all, her film projects have only brought in a handful of great triumphs throughout her long-running career (see Ghost, The Color Purple and Sister Act).

Whoopi Goldberg

Often we load actors with projections or mistake them for the characters they breathe life into. With Whoopi, there is no question that her characters are the recipients of a fully formed, larger-than-life spirit. We see in her a friend, a mentor, someone who makes us laugh, and in her voice we hear clarity, confidence and warmth. When accounting for her early struggle with drug addiction, she once explained: “you find that it’s easier to live outside of life”. In the end, Whoopi chose to live inside of life – and that’s worth admiring.

Eleni Stefanou

Marion Grierson (1907-98)

Marion Grierson’s Around the Village Green (1937)

Marion Grierson was a writer, editor, producer and director who made most of her documentary films at the height of the British documentary movement in the 1930s. Her work displays a wonderfully assured lightness of touch and a sophisticated array of visual and sound techniques – never more so than in Beside the Seaside (1935), which beautifully observes the pleasures of a coastal excursion. Post-lunch torpor is suggested by slow-motion dancing which segues into perkier night-time stepping out; and overlapping snippets of dialogue wittily convey the diversity of seaside day-trippers.

The younger sister of John Grierson, the founding father of the British documentary movement, Marion learned how to edit from him, using techniques inspired by Soviet montage films. She married fellow documentarist Donald Taylor, and all but withdrew from film work after their first child was born – as was the expectation of the time.

Ros Cranston

Julie Harris (1921-)

Julie Harris

From Ursula Andress’s pink feathered negligee in Casino Royale (1967) to Dame Edith Evans’ moth-eaten fur coat in The Whisperers (1966), Julie Harris clothed film stars for every occasion for over 50 years. An Oscar win for Darling in 1966 cemented her reputation and she carried on designing for film and TV into her 70s.

Harris showed a profound understanding of the importance of costume not just to the film but to the actor, helping them feel as much as look the part. Balancing the mood of a scene with each actor’s figure and personality, her use of colour and fabric was always creative, sometimes audacious – such as the fur bikini Diana Dors modelled at the Venice Film Festival. Whether designing for Bond girls or the Carry On team, Julie Harris blended an attention to detail with wit and originality, a combination which kept her at the top of her profession for most of her long career.

Josephine Botting

Edith Head (1898-1981)

Costume designer Edith Head occupies an unassailable position in the Hollywood pantheon, holding the record for the most Oscars won by any individual woman – eight in total. In a career spanning six decades, she was also nominated 35 times and was responsible for some of the most iconic frocks in film history.

Edith Head

Head dressed some of the biggest stars that graced the screen, including Barbara Stanwyck, Gloria Swanson, Grace Kelly and Elizabeth Taylor, and helped to shape character through costume in such films as A Place in the Sun (1951), Vertigo (1958) and The Birds (1963). But she also understood that her own image and reputation were vital, and while other designers were just as well known, and perhaps even more influential, Head was (and still is) by far the most recognisable of all of them, with a distinctive, trademark ‘look’ that was entirely her own, even earning her own Google Doodle in 2013.

Sarah Currant

Storm de Hirsch (1912-c.2000)

Storm de Hirsch

I love the fearless films of Storm de Hirsch because they exploit cinema for ritual and mythic purposes to draw you into a very liminal psychic space. These hypnotic mirages in 16mm combine live photography as abstract fragments of the unconscious with the transfiguring effects of optical tricks and hand-painting directly onto celluloid. They constitute a body of work in search of transcendence beyond the repressive confines of gender into a boundless cosmic sexuality.

Though five years Maya Deren’s senior and very different in style and temperament, she was her natural (and under-acknowledged) successor, taking a similarly mythic pseudonym and making her first film in 1963, two years after Deren’s death, when very few women artists were embracing cinema. Influenced by the direct spiritual experiences of tribal cultures, films including Peyote Queen (1965) and Divinations (1964) are invaluable contributions to the history of visionary film.

Stuart Heaney

Kim Hunter (1922-2002)

Kim Hunter (real name Janet Cole) first came to the attention of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger at a screening of Tender Comrade in 1943 while they were casting for their next film. In the summer of 1945, as war in Europe was about to end, Kim Hunter risked coming to England to begin filming A Matter of Life and Death (1946) at Denham Studios. Hunter travelled from Baltimore on a 30-hour journey by plane and train (as reported in the Picture Post and Life Magazines) to take up the starring role as the USAAF radio operator who falls in love with RAF pilot Peter Carter (David Niven). Hunter displayed a tender and refined temperament that was perfectly suited to convince the heavenly court that her love for Peter was heartfelt.

Kim Hunter with David Niven in A Matter of Life and Death (1946)

Thereafter, Hunter took a break from films but she made a spectacular comeback in 1951 to play alongside Marlon Brando as the long suffering wife of Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), winning both an Academy Award and a Golden Globe for best supporting actress. Later on, she starred alongside Charlton Heston in Planet of the Apes (1967).

Nigel Arthur

Maria Klonaris (1950-2014)

Buddha Boy (1995)

Early 2014 saw the sad passing of Maria Klonaris. Of Greek origin but based in Paris, with collaborator Katerina Thomadaki, Maria Klonaris was responsible for some of the most radical feminist and transgender art and film ever created. Klonaris and Thomadaki were founders of what they called the Cinema of the Body.

Fiercely independent, shooting on Super-8 and controlling every aspect of production, the Cinema of the Body questioned the notion of a received identity. Their practice was a dialectic one where the image affects the body and in turn, the body affects the image, each bringing about change in the other. Their most compelling work, The Angel Cycle, reworked again and again an old medical photograph of a blindfolded hermaphrodite; seeing this intersex person as the herald to a new way of being without gender categories that rule every aspect of our lives. That they were two women artists working together made this practice possible. But no longer and we are so very sad.

Helen Dewitt

Kim Longinotto (1950-)

“You’re very welcome to acquire any of the films… I just love them to be screened” was Kim Longinotto’s reply when I first approached her about depositing her films in the BFI National Archive back in 2012. If a big fan then, having had the opportunity to become more acquainted with her work by virtue of acquiring it into the BFI’s documentary collection over the past year, my admiration for this extraordinary filmmaker has reached new heights.

Kim Longinotto

Longinotto has dedicated her career to illuminating the plight of the persecuted, and her films show some of the most harrowing scenes of abuse ever committed to the screen. But, far from portraying victims, her films are populated with rebels, pioneers and survivors (mostly women and children) afforded the space to recount their incredible stories. Beyond the artistry and storytelling prowess (which has been recognised by the likes of BAFTA and Sundance) only a filmmaker with such generosity of spirit and genuine interest in others could elicit such trust in her subjects.

Catherine McGahan

Ida Lupino (1918-95)

Ida Lupino is best known as an intelligent, unusually versatile actor, her range embracing tough and tender, classy and brassy, cool and caring, feisty and fatale in gems like They Drive by Night (1940), High Sierra (1941), The Man I Love (1947), On Dangerous Ground (1951) and The Big Knife (1955). But this Hollywood star – born in London to comedian Stanley Lupino and actor Connie Emerald – was also for many years the only woman of note working in a male-dominated area of the creative arts: she not only co-wrote and co-produced but directed a number of very impressive movies.

Ida Lupino in On Dangerous Ground (1951)

Their subject matter was often audacious: pregnancy outside of marriage (Not Wanted, 1949), rape (Outrage, 1950), overweaning maternal ambition (Hard, Fast and Beautiful, 1951) and the possibility of loving more than one person (The Bigamist, 1953). The Hitch-hiker (1953), meanwhile, is as taut a thriller about a psychokiller as you could wish for. In short, Lupino refused to conform to type or expectations; no wonder the likewise pioneering and free-spirited jazz bandleader Carla Bley felt inspired to name one of her loveliest and most haunting melodies after her.

Geoff Andrew

Lindsay Mackie and Beeban Kidron

Although Lindsay Mackie and Beeban Kidron have distinguished careers in journalism and filmmaking, it’s as co-founders of the charity FILMCLUB that I admire them most. Their desire to show how film can educate and inform, as well as take you into a world of imagination, has resulted in a network of over 7,000 free after-school clubs, attended by over 200,000 children across the UK. A whole new generation is finding pleasure in classic films as well as modern blockbusters, and for many it can be their only opportunity for a cinematic experience, whether for reasons of poverty or of complex special needs.

Beeban Kidron filming Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (2004)

The success of FILMCLUB can be measured now, but it will truly only be understood in years to come when many more young people share Mackie and Kidron’s passion for film, whether as cinemagoers or working in the business themselves.

Pam Rostron

Samira Makhmalbaf (1980-)

Born in Tehran in 1980, Samira Makhmalbaf would later make what may be the most accomplished feature film ever made by a teenager. Directed when she was just 17 years old, The Apple (1997) is the true story of two young sisters kept in confinement by their strict religious parents.

Samira Makhmalbaf

Samira had observed and assisted her father – the great director Mohsen Makhmalbaf – for years, appearing in front of the camera in a cameo in his film The Cyclist (1987) when she was seven. But his mentorship only goes so far to explain the originality and maturity of this startling directorial debut – its critique of oppression, its tenderness towards the characters, its delicate juggle between fiction and reality. Blackboards (2000) and At Five in the Afternoon (2003) confirmed her talent, but she’s gone quiet after 2008’s Two-legged Horse, which was filmed in Afghanistan after the Iranian government refused her permission to film at home. Now 34, she regularly appears on juries at film festivals around the world, but one hopes we’ve not heard the last from Samira Makhmalbaf as director.

Samuel Wigley

Elaine May (1932-)

With two of her three films as director widely ignored and her final one hailed as one of cinema’s greatest turkeys, the films of Elaine May remain unforgivably overlooked. A New Leaf (1971), in which May also stars, sees Walter Matthau at his grumpiest, out to bag a rich young bride. It wrapped kitsch comedy, social satire and complex characters in a polyester bow long before Wes Anderson thought to. Effortlessly jumping genre to gritty underworld pathos, Mikey & Nicky (1976) sees Peter Falk and John Cassavetes as dirty hoodlums drowning in paranoia. It perfectly nails the tragedies of primal machismo while the supporting cast paint a brooding portrait of grim femininity.

Elaine May in A New Leaf (1971)

The last film May wrote and directed was Ishtar (1987), which contains idiosyncratic character acting at its funniest. It was little seen yet widely mocked – a response which apparently robbed us of the potential for further great films.

Jon Spira

Asta Nielsen (1881-1972)

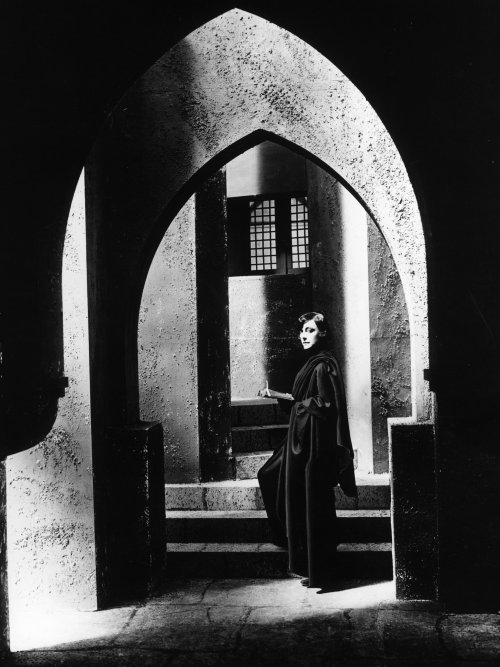

Asta Nielsen in Hamlet (1921)

In the year that our thoughts are considering the events of 100 years ago, we find in the cinema of the time a brilliant and astonishing woman. Asta Nielsen, born into hardship in Copenhagen, transcended expectations by studying at the Royal Danish Theatre and going on to become one of the first international film stars. Having found success and some notoriety with her first film, Afgrunden (The Abyss), a tragedy directed by her first husband Urban Gad in 1910, Nielsen moved to Germany and with Gad and producer Paul Davidson founded a new studio: the International Film-Vertriebs-Gesellschaft. Nielsen proceeded to star in some 70 films during the silent era, dominating German silent film and in 1914 became cinema’s highest paid star, drawing an $80,000 salary.

She’s credited with pioneering a naturalistic, uninhibited style of acting, moving away from the prevalent gestured, theatrical style. She also possessed admirable range, playing every conceivable kind of character from every social strata, regularly taking roles that involved gender complexity. Perhaps most notable is Sven Gade’s daringly modern 1921 production of Hamlet, which sees Asta in a role that teases and questions established notions of gender and sexuality. It’s a typically confident performance.

Having retired from film with the advent of sound movies, Nielsen was courted by Adolf Hitler, who tried to persuade her to return to film under the auspices of Nazi power. She declined and returned to Denmark, and later, during the Second World War, provided money to an effort to assist Jews in Germany.

Stuart Brown

Archie Panjabi (1972-)

Archie Panjabi in Siren Spirits (1994)

Archie Panjabi probably came to most people’s attention playing equally mouthy sisters, Meenah and Pinky, in East Is East (1999) and Bend It like Beckham (2002). She stood out in both, adding humour and warmth to otherwise obnoxious characters, but it was a few years later, as the title character in Yasmin (2004), when she really came into her own. Panjabi played a British Asian in an arranged marriage, torn between family loyalty and her identity in the modern world. It was admirable to take on a role which dealt head-on with Islamophobia in the wake of 9/11, and Panjabi’s performance was mesmerising.

Then, rather than allowing herself to be typecast, she took on a character defined by sexual and moral ambiguity rather than race: the ballsy private investigator Kalinda in US drama The Good Wife. She made the role her own and bagged an Emmy to boot. Away from the screen she’s been politically active and philanthropic (as the face of Amnesty’s Stop Violence Against Women campaign), and to my mind is just as kick-ass as the women she portrays.

Liz Parkinson

Dolly Rudeman (1902-80)

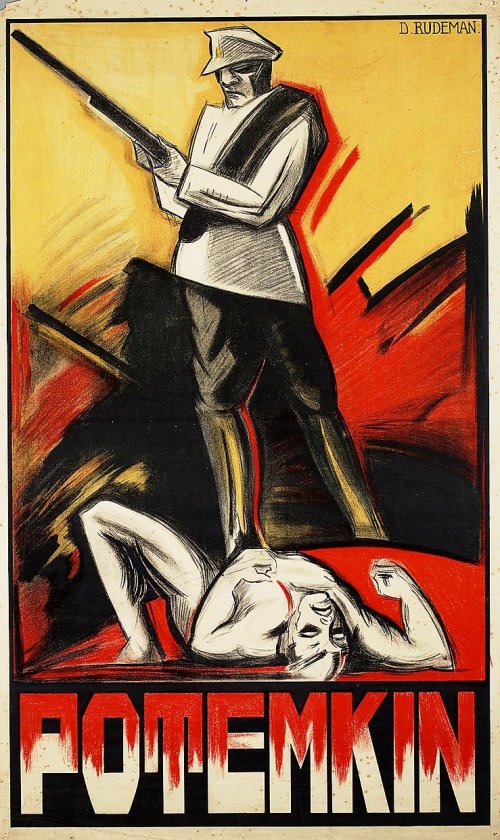

Dolly Rudeman's poster for Battleship Potemkin (1925)

I admire Dutch graphic artist Dolly Rudeman not just because she was a rare example of a female film poster designer working in the silent era and the 1930s (a fact her signature ‘D. Rudeman’ concealed), but also because her posters were so different to those of her male contemporaries (sadly only 120 designs survive). Consider her striking creation for Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), a colourful and expressionist hand-painted design which mourns the horror of the Odessa steps sequence and which couldn’t be more distinct from the Russian Constructivists’ stark, bloodless interpretations of the film. Rudeman specialised in acute character studies, particularly of female characters and it was fortuitous that as she began designing in the 1920s, female stars such as Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo rose to prominence.

Rudeman’s most haunting poster was for Victor Sjöström’s 1928 film The Divine Woman. Only a nine-minute reel of the film now survives, along with Rudeman’s vision of Garbo’s melancholic face floating in a sea of blue. Despair, anger, fear and joy are sentiments commonly sketched by poster artists to sell films, but rarely does real sadness figure so prominently. In contrast, the American poster for the release promised a movie of cocktails and gaiety.

Isabel Stevens

Helma Sanders-Brahms (1940-)

Helma Sanders-Brahms

Helma Sanders-Brahms came to prominence in the 1970s, one of a remarkable number of women directors whose fresh perspective and fearless vitality helped to invigorate the New German Cinema. More cherished abroad than at home, her feminist politics, radical subjectivity and sympathy with oppressed groups have provoked responses ranging from irritation to outrage.

In Germany, Pale Mother (1980), her most celebrated film, a young woman and her small daughter confront the horrors and hardships of war together, only to find that their close relationship is brutally disrupted and their independence destroyed when the men return from fighting. At the time of its Berlin Film Festival premiere, the film was ferociously condemned by German critics for its uncompromising focus on female experience and for daring to portray the Second World War as a period of liberation for women. As a result, the film was cut by 30 minutes for its theatrical release, and only now, almost 35 years on, has the director’s cut (151 minutes) finally been restored. With a brave and brilliant performance from Eva Mattes in the central role, Germany, Pale Mother – lyrical, harrowing and thought-provoking – is ripe for rediscovery by a new generation.

Margaret Deriaz

Thelma Schoonmaker (1940-)

Picture any classic Scorsese scene from the last 30 years and it will have passed through the hands of Thelma Schoonmaker. Schoonmaker met Scorsese at New York University in the 1960s and, after helping him edit a student project, they began a long lasting creative partnership. Following a dispute with the unions, she was able to join Scorsese full time as his editor on Raging Bull (1980) and they have worked together ever since.

Thelma Schoonmaker

Schoonmaker is always keen to share the credit, but there’s no denying her contribution to shaping stories and crafting performances from improvised scenes. She has mastered the industrial shift from film cutting to digital editing and even ventured into 3D with her work on Hugo (2011). Scorsese and Schoonmaker’s most recent collaboration, the audacious The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), shows that there is much more to come. Schoonmaker also serves as guardian to the legacy of her late husband, director Michael Powell, so it’s no surprise that, when once asked how she relaxed, she replied “I don’t!”

Lisa Kerrigan

Leila Stewart (1893-1939)

Leila Stewart photographed by her husband, Sasha (1925)

Credit: Sasha/Getty Images, courtesy Getty Images

Leila Stewart (née Lewis) was a pioneering figure in the often overlooked area of film publicity. She carved out a career for herself during the 1910s while also promoting the early film business as a sphere that could offer a range of fascinating career opportunities to women. In 1918 she set up an early cinema club in the form of the Stoll Picture Theatre Club. The club hosted serious talks on aspects of the film industry as well as glitzy star-studded events and studio tours. The following year, Leila married photographer Alexander Stewart (‘Sasha’), and her connections in the industry almost certainly would have helped launch him as a renowned photographer of high profile stage and screen personalities.

During her career, Leila also mentored a host of other talented publicists such as Catherine O’Brien and Margaret Marshall. When she died in 1939, obituaries lamented the loss of “a great publicity chief, the acknowledged head of her profession”.

Nathalie Morris

Christine Vachon (1962-)

Christine Vachon

Sneaking downstairs after my parents had gone to bed as a teenager to watch gay-themed films, often on Channel 4, is one of the formative memories from my adolescence, and filmmakers like Todd Haynes, Rose Troche and Tom Kalin became names to follow. But many of the films of the subversive New Queer Cinema movement of the 1990s would never have been made without the formidable support of Christine Vachon.

Poison (1991), Swoon (1992) and Go Fish (1994) have entered the queer cinema canon, and since then Vachon has produced a string of boundary-pushing favourites, from the edgy humour of Happiness (1998) to the devastating heartbreak of Boys Don’t Cry (1999), the unique rock musical Hedwig and the Angry Inch (2001) and even the most underrated film of John Waters’ career, the outrageous A Dirty Shame (2004). Thanks to her, cinema, queer or otherwise, is much the richer.

Alex Davidson

Sheila Whitaker (1936-2013)

Sheila Whitaker died last summer. This is not an obituary – that has been eloquently covered already – but a simple statement of admiration, thanks and celebration of her extraordinary achievements in film. Sheila was a stills archivist, a writer and editor (of the radical film journal Framework) and in 1979 took over the programming of the Tyneside Cinema before moving to the BFI to head up programming of the National Film Theatre and the London Film Festival in 1984, also establishing the London Lesbian & Gay Film Festival (now Flare).

Sheila Whitaker

There were other female programmers in the UK at the time, but I’m sure that Sheila’s prominence benefited all of us by spearheading a sense that it was not unusual for women to take the lead in presenting a culturally diverse cinema. She was of an older generation than most of us, but probably younger at heart, while radiating a sense that age didn’t matter as much as passion and a hunger for knowledge. Sheila was political and a feminist with both liberal and subversive tastes, and a love of Doris Day.

At the end of her 20-year tenure at the BFI, Sheila was snapped up by Dubai Film Festival as a programmer, working for them until the end, in addition to continuing to help many others think about film in different ways. Her influence is impossible to measure, as the films that she championed reached massive, diverse audiences, while the people she employed and befriended and advised have gone on to do the same, all over the world. This is her legacy; happy International Women’s Day, dear Sheila.

Jane Giles